Being an oncologist is tough.

Sure, there is the exhilaration of discharging a long-term patient when they have been cured. There is the excitement of working on a new drug or trial that has the potential to make a real difference in patients’ lives. There is also the sadness of saying goodbye to the person who is being seen for the last time before their death.

In between all of the exhilaration and sadness is the mental anguish of wondering “am I making the right decision?” The self-doubt has not gone away even after 20 years of practicing medicine (for me). Everyone talks about “imposter syndrome” when you start your career, though I feel the “self-doubt” part of the imposter syndrome is present in my mid-career, and I hope to have that doubt even at the end of my career. The question of “is it the right decision to prescribe treatment A or B to this patient” is an important one. I tell my trainees that the day I stop asking this question may be the day I lose my humility and make a mistake.

The day we stop asking questions and lose our humility is the day we make our biggest mistake.

-Me

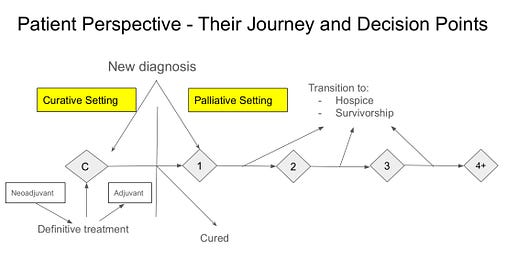

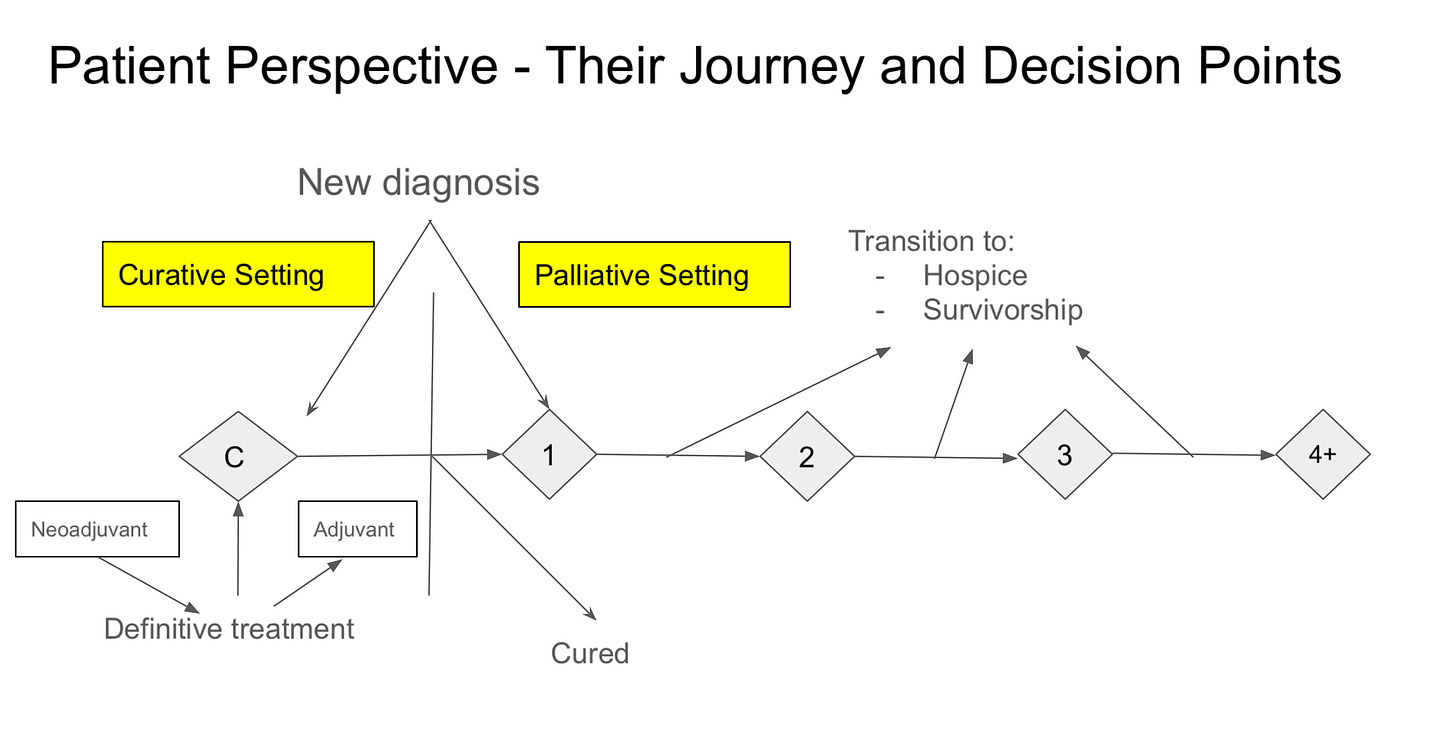

Below is a diagram of how I see a patient’s journey. It begins with a new diagnosis, and we determine (see Oncology 101) if the goal of treatment is cure or palliation. If our goal is to cure, meaning our treatments have “curative intent,” then we consider one or more modalities of therapies (systemic and local). If we are fortunate and the patient is cured, then they are happily discharged from the practice in about 5 years.

If a patient starts the journey and has metastatic disease, or their cancer recurs after curative intent treatment, our goal of their cancer treatment is palliation. We utilize one or more lines of systemic (and add local therapies) to “help patients live for as long and as well as possible.”

Along the journey of palliation, hospice is an option at each decision point (as shown in the figure). In truth, though, it is an option at every decision point, depending on the person being treated. There are times, based on a patient’s overall health status and cancer, we may recommend not to focus on their cancer.

Going back to emotions, I find the hardest decisions for me are starting the first line of therapy and stopping (or not starting) cancer-directed therapies (transitioning to hospice). To my research colleagues, has this been studied? If not, it would be good to study whether different decisions in the patient journey have different impacts on the oncologist and their mental health.

Is it the right decision?

Questioning ourselves on whether we are making the right decision may seem like self-doubt and have a negative connotation. Some may correlate that with a lack of knowledge or experience, which was true at the beginning of my career, or when I did new things. However, that questioning can also have a positive connotation. Having the humility to look up literature, re-read an article, or ask a colleague or mentor to double-check our decisions are good behavior for the sake of our patients. Today, as a mid-career oncologist, the questioning comes from myself, my trainees, and team members. With experience comes the development of “system 1”, or “fast” thinking (this is in reference to “Thinking, Fast and Slow” by Daniel Kahneman). The questioning by others or by self allows time for System 2, or slow and deliberate thinking. (And yes, I am using the word “deliberate” deliberately to remind all of the principles of deliberate practice in meaningful conversations).

One of the advantages of being in an academic practice is that each day a new trainee questions everything I do (or at least I hope they do). They question my assumptions and my routine choices (system 1). There are two ways to respond to this - one is to tell them the superficial answer of why, and another is to look at it from their perspective and understanding and teach them the why (system 2).

I favor the latter and try to do that most of the time. It is challenging as the questions they ask are similar year after year; what is the known pathophysiology of the disease? What is the known pharmacology of regimen A or B? What are the risks and benefits of regimens A and B? What is the data behind regimens A and B?

Emotions behind the decision

Earlier, I said the hardest decisions were to start the first line of therapy and stop therapies. As I reflect on the why, I see how it impacts the patients and families.

When we are deciding on the first line of therapy, patients have to process a significant amount of information, such as:

What is my cancer?

Where is my cancer?

What does it mean for me?

What are my treatment options, what should I expect, and how do I make the decision?

They have to digest all of this cognitive information whilst balancing their emotions.

When deciding to stop cancer-directed therapies, patients have to process a different set of emotions. Emotions such as (anticipatory) grief and sadness or loss.

So, why are these times more challenging for me?

When I see a patient for the first time and I recommend focusing on quality of life without prescribing systemic therapies, there is always that question in the back of my mind; what if I prescribed something, and it worked?

When I have a long-term relationship with a patient, and I recommend stopping cancer-directed therapies and focusing on comfort, there is a sense of loss and sadness. Getting to know a person for a period of time — getting to know their goals in life, getting to know their family - implies we are forming a bond. Even if the rational mind understands that it is a temporary bond, there is still sadness when saying the last goodbyes. There is anticipatory grief of not seeing them again, of their death.

Why talk about emotions?

There are two main reasons to talk about emotions.

First and foremost, it is for us. I get asked often, “How do I do this? How do I deal with having to give bad news?” Behind those questions is the acknowledgment of the potential negative emotions associated with having these challenging conversations. Not only regarding the negative emotions, but also acknowledging the impact of these emotions on other parts of life. There are concerns about burnout due to the accumulation of these feelings.

Second, it is for our patients. It is about their emotions. The bond we make works both ways. Just as hard it is for us to say “goodbye,” I find (and research suggests), it is hard for patients to give negative information to us. That includes reporting the side effects of the treatments we provide. It also includes not wanting to disappoint us by “stopping treatments.” (See one of my colleagues, Dr. Login George’s work published here).

Thus, these emotions (which are inherently good) from both patients and oncologists can lead to making bad decisions. Decisions such as continuing ineffective therapies, or continuing the next line of therapy with a low likelihood of benefit because it is hard to say “no” to the other person.

These poor decisions can impact a patient’s quality and quantity of life. Acknowledging emotions is the first step in ensuring that we make decisions that are cognitive (based on facts and objective findings) and not emotion-driven. It also allows us to make sure that if decisions are made based on emotions, they are not “avoidance” emotions.

A patient avoiding telling the oncologist the truth about how they are feeling.

An oncologist avoiding giving bad news because they like their patient.

Both the patient and the oncologist avoid discussing end-of-life care planning because there may be disappointment in the other person and feelings that the other person is “giving up”.

These negative emotions also play a role within the family complex as well, leading to similar avoidance behaviors.

A patient and family avoiding doing life tasks.

A patient avoiding end-of-life care planning.

Understanding the emotions involved and their potential impact on decision-making is important. Every one of our actions has the potential for positive and negative outcomes. The Meaningful Conversations curriculum focuses on building rapport, listening, reflecting, and addressing emotions to allow us to provide patient-centered care. This rapport and care allows our patients to open up to us and tell us their deepest and darkest fears (the good), and it also makes them want to avoid disappointing us (it's their humanity), which can make it harder for us to provide this goal-oriented care.

So what do we do with this information?

For today, take a pause and reflect on “how hard it is to be an oncologist.” As I would say in many of my talks, “it f*%&ing sucks.”

I want to be present for this moment and not focus on “fixing it.” However, I promise to give you some thoughts on it in the next few posts.

This post, along with the past few posts (Be Like Sheldon, Be Like Sheldon Part II, Walking the Walk), are focused on my oncology fellows. As some of them will go out in their practice in July, I hope that they will remember these lessons to have a productive and fulfilling career.

Not being a physician, I chose to read further between the lines. Let's never take for granted just how challenging and emotional our careers are. Let's recognize that we, too, are human. Let's understand what our colleagues go through and be supportive of the human element. To demonstrate my point, while I train my colleagues to be supportive of any question or opportunity to break ties in treatment care decisions by helping with co-morbidity assessments, abnormal labs, medication interactions or social determinants; that is just being there for the clinical side. We must be there for the emotional side of patient and provider care. So, Dr. Saraiya, "how are you?"

Great post Dr Saraiya